Introduction

Let’s examine CRPS throughout history: what it has been called, the major historical events that brought greater awareness of and understanding about the condition, and how the stories and stereotypes of the past can impact us today.

Originally seen as a condition that primarily affected young men suffering from high-velocity impact wounds—such as gunshots—during times of high emotional turmoil from the battlefield, Complex Regional Pain Syndrome has historically been considered a soldier’s disorder. This perspective has changed in recent years as the medical community has learned more about the condition and now understands that it affects at least three times as many females as males and that the largest age demographic of those impacted are those in their middle-ages.

Let’s dive in.

1570s Huguenot Wars: Ambroise Paré and King Charles IX of France

During the mid-1500s, barber surgeon Ambroise Paré—now recognized as the father of modern surgery—was doctor to the royal French family, the House of Valois;1, 2 Paré was a Huguenot (what we would today call a Protestant or more specifically a Calvinist), and he had risen through the ranks during his time in military service despite the increasing political and religious tensions from the majority Catholic country.3

Paré is credited with first identifying Phantom Limb Syndrome, as well as a severe pain condition that in modern times we would likely diagnose as CRPS.4, 1, 5, 6, 7, 8, 2 Paré (1510-1590) served as physician for four French kings during his lifetime, but the one relevant to this article is King Charles IX (1550-1574), a young man with temperamental physical and emotional health who reigned during the tumultuous years of the Huguenot Wars when the tensions between Catholics and the Protestants boiled over into open political violence.3

In 1570, the same year the Edict of Saint-Germain established a temporary peace and ended the Third French War of Religion (1568-1570), King Charles IX—then 20 years old and king for a decade after the deaths of his father and older brother—developed a severe, persistent, burning pain with muscle loss and contractures in his arm after a bloodletting to treat smallpox.1, 5, 9, 7, 10, 2 Paré described this in his 1598 book “Les Oeuvres ď Ambroise Paré”—or The Works of Ambroise Paré—in “Chapter XXXVIII. Of the cure of wounds of the nervous parts”.10, 3 Paré treated the king’s malady in a similar manner to wounds from soldiers on the battlefield: turpentine, aqua vita (a liquor), rose oil, egg yolk, and wrapping the arm in linen soaked in oxycrate (water and vinegar).3 After three months of treatment, the king’s injury was considered “perfectly healed.”3

Two years later in 1572, when the Catholics slaughtered multiple thousands of Huguenot Protestants across France during the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, King Charles IX protected his doctor by hiding Paré in the king’s own closet.1 Charles IX died at age 23 of tuberculosis, and with his death the conflict between the Catholics and the Huguenots solidified and further increased. The French Wars of Religion continued on and off until from 1562-1598, often in approximately two year stints, and were followed a generation later by the three Huguenot Rebellions in the 1620s.

The personal history of Charles IX, the influence of his dominating powerhouse of a mother Catherine de Medici on his reign and national politics, and how the effects of the societal turmoil and tension (particularly the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre) impacted Charles on a personal level are fascinating, thought-provoking, and likely will receive their own article at some point in the future, but they are outside the scope of this piece.

1810s Napoleonic Wars: Alexander Denmark’s Case Report

Though in the late 1700s there is the minor figure of Sir Percival Potts, a British surgeon and one of the founders of orthopedics, who recognized weakness and burning pain in injured extremities, the next major figure in CRPS history is British military surgeon Alexander Denmark in 1812-1813. He was the first to specifically document a case of causalgia.3

Denmark worked at the Royal Navy Hospital Haslar in Hampshire; he wrote a case report of a soldier suffering from a gunshot wound from the Third Siege of Badajoz in Spain during the Peninsular War, one of the bloodiest engagements in the entirety of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815, and a European-wide conflict extending from the French Revolutionary War 1789-1799)—with the victorious British troops furious at the losses sustained during the siege, soldiers ignored commands of their officers to drunkenly pillage, terrorize, injure, rape, and murder hundreds of local civilians.11, 10, 3

Denmark treated a soldier shot through the upper arm, and the man’s wound healed quickly. However, Denmark would “always” find the soldier “with the forearm bent and in supine position and supported by the firm grasp of the other hand. The pain was of a ‘burning’ nature, and so violent as to cause a continual perspiration from his face.”11, 10, 2 Denmark linked his patient’s pain to damage to his radial nerve from the gunshot wound and described the condition as “violent” and “burning” with the nerve appearing discolored, “blended,” “intimately attached,” “twice its natural diameter,” and “with a ball firmly embedded”.2, 3 Eventually, the soldier’s arm was amputated and his suffering ceased.10, 3

Denmark’s 1813 case report was ignored, but a few decades later Weir Mitchell entered the scene during the American Civil War and the condition Denmark characterized became a fully fleshed condition recognized by many physicians.11, 2, 3

Civil War: Weir Mitchell and Causalgia, and Charcot and Hysteria

Silas Weir Mitchell (1829-1914), at the time considered first among physicians and now considered the father of modern neurology, is likely the most well-known figure in CRPS history, and for good reason.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 3 In addition to his focus on causalgia—which comes from the Greek for “heat pain” or more aptly “burning pain” or “being burned pain”, and from the same root as caustic—Mitchell is credited with his work with Phantom Limb Syndrome, motor palsy, toxicology, the signs of a healing nerve, and distinguishing between the degree of nerve injury and its associated healing time, as well as the now-rejected rest cure.17, 15, 18, 19, 1, 16, 3 Mitchell wrote several seminal works on nervous system conditions and had an excellent skill with written communication that got peers and laymen to pay attention to what he had to say; he had a particular focus on causalgia and brought it into the mainstream of medical scrutiny and broader public awareness.12, 14, 1

In 1862-1865, Mitchell was assigned to Turner’s Lane, a 400 bed US Army Hospital in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, also given the moniker “Stump Hospital” due to the type of wounds treated there, which were primarily for “nervous diseases”.20, 4, 17, 14, 18, 9, 8 In particular, Mitchell treated a great many soldiers from the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863—considered to be the bloodiest and most costly battle of the American Civil War, as well as its turning point, as from that conflict on the Confederates were on the defensive and never invaded the North again. 20, 4, 3 The wounded soldiers from Gettysburg led to groundbreaking research, particularly around the condition of causalgia. 20, 4, 1, 5, 3, 21

Mitchell took a great interest in the pain of these soldiers and wrote: “It is a form of suffering as yet undescribed, and so frequent and terrible as to demand from us the fullest description. In our early experience of nerve wounds, we met with a small number of men who were suffering from a pain which they described as “burning,” or as “mustard red hot,” or as “a red-hot file rasping the skin.”” 20, 4

Mitchell described how: “Usually the pains from nerve hurts are either aching, shooting, or burning…prickling pains…jagging, shooting, and darting pain…principally burning…The burning arises…almost always during the healing of the wound… Its favorite site is the foot or hand…the palm of the hand or palmar face of the fingers, and on the dorsum of the foot; scarcely ever on the sole of the foot or the back of the hand. When it first existed in the whole foot or hand, it always remained last in the parts referred to…if it lasted long it was finally referred to the skin alone. The part itself is not alone subject to an intense burning sensation, but becomes exquisitely hyperaesthetic, so that a touch or a tap of the finger increases the pain…The skin affected in these cases was deep red or mottled, and red and pale in patches. The subcuticular tissues were nearly all shrunken and, where the palm alone was attacked, the part so diseased seemed to be a little depressed, firmer and less elastic than common. In the fingers there were often cracks in the altered skin, and the integuments presented the appearance of being tightly drawn over the subjacent tissues. The surface of all the affected parts was glossy and shiny as though it had been skillfully vanished. Nothing more curious than these red and shining tissues can be conceived of. In most of them the part was devoid of wrinkles and perfectly free from hair…this pain was an associate of the glossy skin…The burning comes first, the visible skin-change afterwards…feeble power…joints became swollen…bent at a right angle…molded to the curve of the chest on which it lay.”4, 1, 22, 3

He wrote how it could impact a soldier’s mental and emotional state: “Under such torments, the temper changes, the most amiable grow irritable, the soldier becomes a coward, and the strongest man is scarcely less nervous than the most hysterical girl… As the pain increases, the general sympathy becomes more marked. The temper changes and grows irritable, the face becomes anxious, and has a look of weariness and suffering. The sleep is restless, and the constitutional condition, reacting on the wounded limb, exasperates the hyperaesthetic state, so that the rattling of a newspaper, a breath of air…the vibrations caused by a military band, or the shock of the feet in walking, gives rise to increase of pain. At last…the patient walks carefully, carries the limb with the sound hand, is tremulous, nervous, and has all kinds of expedients for lessening his pain.”4, 22

And how soldiers would attempt to mitigate their pain and distress, particularly noting the use of water dressings: “Exposure to the air is avoided…with a care which seems absurd, and most of the bad cases keep the hand constantly wet, finding relief in the moisture rather than in the coolness of the application…Two carried a bottle of water and a sponge, and never permitted the part to become dry…in two cases the men found ease from pouring water into their boots…wet his stockings… One wet the sound hand when obliged to touch the other.”4, 22, 3

Mitchell’s more personal interspersed views included phrases such as: “Perhaps few persons who are not physicians can realize the influence which long-continued and unendurable pain may have upon both body and mind… Perhaps nothing can better illustrate the extent to which these statements may be true than the cases of burning pain, or as I prefer to term it, causalgia, the most terrible of all the tortures which a nerve wound may inflict…a state of torture which can hardly be credited… Of the special cause which provokes it, we know nothing, except that it has sometimes followed the transfer of pathological changes from a wounded nerve to unwounded nerves, and has then been felt in their distribution, so that we do not need a direct wound to bring it about.” 20, 4, 2, 22, 3

He was one of the first to use opiate tinctures to treat causalgia, and he created the hypodermic syringe to perform cocaine nerve blocks.23, 3 He commented on opioid tolerance developing when taken long-term to manage chronic pain: “For the easing of neurotraumatic pain [referring to causalgia] the morphia salts…are invaluable… When continuously used, it is very curious that its hypnotic manifestations lessen, while its power to abolish pain continues, so that the patient who receives a half grain or more of morphia may become free from pain, and yet walk about with little or no desire to sleep.” 23

Together with his colleagues, George Morehouse and William Keen, Mitchell published three books on what he learned from his time at treating soldiers at Turner’s Lane: “Gunshot Wounds and Other Injuries of Nerves” in October 1864, “On Disease of the Nerves, Resulting from Injuries” in 1867, and “Injuries of Nerves and Their Consequences” in 1872; he was a prolific author and published a great many personal works throughout his life, including medical texts, short stories, and poetry.12, 20, 13, 24, 17, 14, 11, 25, 1, 6, 8, 10, 26, 2

“Gunshot Wounds and Other Injuries of Nerves”—which contains the first distinct descriptions of causalgia, phantom limb, and ascending neuritis—quickly became the definitive authority on nerve injuries after its release, with Yale University praising its “originality of thought” and “clarity of exposition”.12, 18, 25, 27, 28, 9, 6, 22, 3 Mitchell was preeminent in nerve injuries with neurology patients being referred to him so regularly that he specialized in the new field of Neurology, presided over the American Neurology Association, and his writings have held up to the test of time so well that his work was reprinted on its centennial anniversary.12, 17, 18, 2 His work had a massive impact on how nerve injuries were treated during World War I.13

In 1866, a year after the end of the American Civil War, Mitchell anonymously published a 35-page short story in the Atlantic Monthly, which was the most popular magazine in the country at the time.14, 29, 25 “The Strange Case of George Deadlow” went out to the average American home and told the fictional yet medically accurate tale of a Civil War Union lieutenant who had some medical background due to helping his doctor father and attending some medical lectures.14, 29, 25 Lieutenant Deadlow tells his experience in first person and describes getting shot in both arms then captured by Confederate soldiers.14 Within an hour, he develops excruciating pain in his deadened right arm, which gets progressively more severe until even the rebel soldiers become alarmed.14

Brought to a Confederate hospital, his arms are treated, but the pain in the right one never improves.14 After six weeks, he is provided an amputation of his right arm without anesthetic; he finds it so relieving that he is asleep before the surgery finishes.14 He is part of a prisoner exchange and soon back in the fight; he is later shot again and loses both his legs to an on-the-field amputation, high up on the thigh.14 He experiences sensations of his legs as if he still had them.14

Taken to a military hospital to recover, he develops gangrene in his one remaining arm that had never fully healed, and his last limb is amputated at the shoulder due to a repeatedly opening artery.14 He continued to feel the left hand as if it were still attached, particularly the left pinky finger.14 He is later transferred to Turner’s Lane “Stump Hospital” where he meets hundreds of other soldiers in similar situations to himself.14

While Mitchell never directly used the terms causalgia or phantom limb in “The Strange Case of George Deadlow”, he brought an accurate description of the conditions into the hands of over 50,000 American households or approximately one in every 130, and he did so in a compelling, engaging way that was relevant to the new world American citizens were living in as their sons, husbands, fathers, cousins, and friends returned home from a nation-altering war without limbs or with severe, difficult to understand nerve injuries.14, 29

More controversially, Mitchell developed two separate treatments for hysteria and neurasthenic neurosis (aka, nervous depression, nervous exhaustion, weakness and fatigue)—diagnoses considered to have “moral and physical components” and be psychogenic—based on sex.4, 19, 30, 31 For men, the West Cure sent men into the great outdoors to spend time being “vigorously” active in nature and were told to write about the experience.30 Women were prescribed six to eight weeks of the Rest Cure and prohibited from writing, painting, and reading and were instead confined to lengthy and highly restrictive isolation of bed rest, electrotherapy, massage, and a high calorie diet.4, 30 The Rest Cure is today rejected by medical practice, but it was accepted and utilized for decades and seen as a treatment option that did not include medications.19, 30 Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper” is a famous short story by a woman who had received the Rest Cure from Mitchell directly.4, 30

In the 1880s, French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot posited that hysteria minor (an umbrella term for several conditions that included causalgia’s fixed dystonia and dystonia-related movement disorders) was a primarily hereditary disorder caused by non-structural lesions in the nervous system of a biochemical or physiological nature, often triggered by environmental factors like physical or emotional stress.32, 10, 33 He definitively separated hysteria from consciously simulated neurologic conditions (malingering).32, 26 In a 1885 lecture on hysteria, he stated: “We have here unquestionably one of those lesions which escape our present means of anatomical investigation, and which, for want of a better term, we designate dynamic or functional lesions.”33

Charcot considered psychology to be the “rational physiology of the cerebral cortex” where physiology and psychology are “really one and the same” and said in 1890 that the anatomo-clinical method would in the future “suce[ed] in revealing at last the primordial cause [of hysteria], the anatomical cause [emphasis added], which is known presently by so many material effects”. 32 The advent of PET and fMRI technology has demonstrated the “dynamic lesions” the medical apparatus of the late 19th century could not prove, with evidence supporting a “multi-network brain disorder implicating alterations within and across limbic/salience, self-agency/multimodal integration, attentional, and sensorimotor circuits.”34

In the year of Charcot’s death in 1893, Charcot lectured on a young male hysteria patient—the Penhouet case study—where he talked extensively on dreams and the power of auto-suggestion, where an intense mental representation becomes objective reality due to unconscious processes automatically producing pathological signs outside of the patient’s conscious control while they are overwhelmed following a perceived trauma.32, 2, 22 Charcot was a pioneer in the hysteria field in the sense that he promoted that “vigorous” and “solidly built” men could develop hysteria and that it “was not very rare” and he admitted men into the hysteria hospital ward for the first time to study and treat them.35, 32 Previous belief across the medical field was that hysteria was a diagnosis for women and effeminate males.32, 35

Causalgia—considered a soldier’s disorder affecting young, vigorous, solidly built men—often was the result of clear nerve injury, but this was not not always the case, particularly as the 20th century’s knowledge progressed and the majority of cases were recognized to be CRPS-I or those without confirmed, discrete damage to a major nerve, and the fixed dystonia that resulted was considered hysteria minor by some. Charcot drew parallels between causalgia, hysteria, ‘psychical’ shock, and “hysterogenic zones” or hypersensitive points where pressure could trigger a hysterical attack and which today would likely be considered fibromyalgia.35, 36

Charcot’s, Mitchell’s, and Freud’s (a student of Charcot who diverged from his mentor’s position) views on hysteria laid the foundational groundwork for modern day diagnoses like psychosomatic, psychogenic, somatization disorders, conversion disorder, and functional neurological disorder—different names for the same concept. 4, 32, 37, 26, 2 The conversion/functional neurological disorder debate surrounding CRPS began within just a few years of the publishing of Mitchell’s “Gunshot Wounds” and continues to this day, with women and people assigned female at birth often receiving the brunt of the historical stigma, particularly as the recommended treatment for FNDs in modern times is often reassurance, CBT, and physical therapy only. 26

The disbalanced hysteria sex ratio leaning heavily toward females (3-4:1) while the vast majority of physicians have historically been males furthered suspicion of the hysteria/psychogenic diagnosis.33 In modern days, researchers hypothesize that “neuroautoimmune-mediated metabolic disturbances fit well with the functional lesion concept, originally posited by Charcot (1885) to explain the etiological origins of “hysteria.””33 This hypothesis would help explain the disproportionate sex ratio in CRPS, as females are significantly more predisposed to develop autoimmune disorders.37

1900-1938 WWI-era: Sudeck, Leriche, and Algodystrophy

In 1900, five years after the discovery of Xrays, German doctor Paul Sudeck (1866-1945), who had become an expert in the new radiographic technique, presented a paper “Acute Inflammatory Bone Atrophy” to the 29th Congress of the German Society of Surgery which described results of localized bone atrophy that occurs with acute, local limb disorders, often following an infection or a traumatic event, and he posited that inflammation was the cause, which brought about symptoms like rubor (redness), calor (heat), dolor (pain), tumor (swelling), and functio laesa (loss of function). 15, 1, 5, 8, 10, 26, 2, 22, 3 In many cases this bone loss was transient and patients quickly recovered, but for some the condition persisted and became highly disabling and the bone loss more diffuse.1, 10, 22 Bone loss was verified by German doctor Robert Kienbock, who thought the atrophy was due to disuse leading to tissue wastage.2, 22

The term Sudeck’s Atrophy was born the following year, so named by Max Nonne, a student of Sudeck, and it is still a commonly used term for the acute inflammatory reflex atrophy subtype of atrophy; it is sometimes used interchangeably with causalgia, but Sudeck’s atrophy specifically refers to the associated bone loss while the original meaning of causalgia is in reference to the burning pain aspect of what we now consider the broader condition.38, 20, 15, 11, 1, 9, 6, 8, 10, 2, 22, 3 Sudeck’s contribution of inflammation as a cause led to many offshoot terms being related to him as well: Sudeck’s Dystrophy, Sudeck’s Disease, Sudeck’s Syndrome, and Sudeck-Babinski-Leriche Syndrome.10 In 1936, another student of Sudeck, Reider, suggested the term Reflex Limb Dystrophy because of the bone tissue wasting and the way the condition seemed to be caused and maintained by the nervous system, which was shortened to Reflex Dystrophy by De Takats in 1937.8, 2, 22

In 1916-7, the next major developmental understanding came a from case report in Strasbourg—a strategic city on the Rhine River in the Alsace-Lorraine region of France under German occupation in World War I—written by military surgeon and French vascular surgeon Rene Leriche (1879-1955). 15, 1, 10, 26, 2, 22, 3 Strasbourg was just east of Verdun (a treasured French city and symbolically important for national morale), where the one of the longest, bloodiest, and costliest battles of not only WWI but also all of human history took place over the course of ten months in 1916; it was the first time flamethrowers were used in the battlefield and it is estimated between 40-60 million shells were fired during that time, many filled with arsenic. The Battle of Verdun is believed to have caused 1.25 million causalities in the Verdun area. On this backdrop, Leriche treated a soldier with ongoing hand pain and numbness after a gunshot to the armpit; the wound had healed and there were no ischemic signs.1, 10, 3

He noted: “I was struck by the resemblance which the condition had to that of a sympathetic disorder; the cyanosis, the sweating, the paroxysmal nature of the pains, the effect on the general mental state, the reference of painful phenomena to a distance—all pointed in that direction. And, remembering that the sympathetic, in its distribution to the limbs, follows the course of the arteries, I asked myself whether, in those cases of nerve injury complicated by arterial wounds, it was not the injury to the sheath of the vessel that determined their painful and trophic features—the wound of the sympathetic—… Starting from this point, I asked myself whether, by acting upon the perivascular sympathetic, I might be able to succeed in modifying the causalgia… I saw the patient on the 20th June; the upper limb was completely paralyzed—arm, forearm, hand and fingers….dominating everything, was an intense burning pain, concentrated particularly in the palm of the hand and on the pulp of the fingertips.” 22

Leriche drew visual parallels between the soldier experiencing the causalgic condition described described by Sudeck a decade and a half earlier and those with ischemic limbs; ischemic limbs were treated with sympathectomies or cutting of the sympathetic nerves, and so he performed a sympathectomy of a peri-arterial nerve on the soldier on August 27, who experienced less pain by the next day and complete pain relief within two weeks. 15, 1, 10, 2, 22, 3 Leriche termed this foundational involvement of the sympathetic system in neuropathic pain “sympathetic neuritis.”1, 10, 26 He posited that “novicain [a local anesthetic, similar to lidocaine] infiltrations of the paravertebral sympathetic chain” or what we would nowadays call a sympathetic nerve block was an effective treatment for causalgia. 22 In 1937, Leriche wrote ‘La Chirugie de la Douleur’ or Surgery of Pain, where he documented his experiences with the soldiers he treated.2, 22

His discovery brought the sympathetic nervous system into focus in causalgia cases, and sympathetic mechanisms and interrupting sympathetic outflow remained at the forefront of research for the next century.38, 15, 1 Leriche proposed the name algodystrophy, and it is in honor of Leriche’s major contribution that added sympathetic to “Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy” when it was coined later.1, 10, 22 The CPRS names Leriche’s post-traumatic osteoporosis and algoneurodystrophy are also associated with his contributions.10

Mitchell’s Civil War publications on causalgia influenced many WWI physicians.13 Athanssio-Benisty and Tinel studied tremor and movement disorders in relation to causalgia, and often referenced Mitchell and sympathetic origin.13 Purves-Stewart and Evans proposed the term thermalgia in reference to Mitchell’s causalgia.13 Carter focused on causalgia cases and referenced Mitchell.13 Foerster described causalgia but used the term “Reflexschmerz” or reflexpain and did not reference Mitchell.13 Oppenheim focused on muscle innervation and referenced Mitchell’s work on excessive hair growth and glossy skin but did not use the term causalgia, though he described the condition in some of his patients.13 Mitchell’s works were well-known in England and his influence can be seen in French literature; though German physicians describe the syndrome, they did not use the term causalgia nor did they refer to Mitchell.13 This is likely due to the fact that Mitchell’s works were translated into French but not into German.13

It is believed that between 1.3-13.8% of WWI soldiers who experienced peripheral nerve injuries developed causalgia.3 In WWII, the treatment of choice for causalgia was “prompt sympathectomy” as those who received delayed treatment had worse outcomes.3 Pre-operative sympathetic nerve blockade allowed for assessment of the efficacy of sympathetectomy and was even sufficient treatment for some patients; the addition of antibiotics to physicians’ tool kits, new sutures, and new nerve grafting techniques allowed for a reduction in persistent causalgia cases.3

1939-1950 WWII-Era: Evans and RSD, Foisie and Arterial Vasospasm

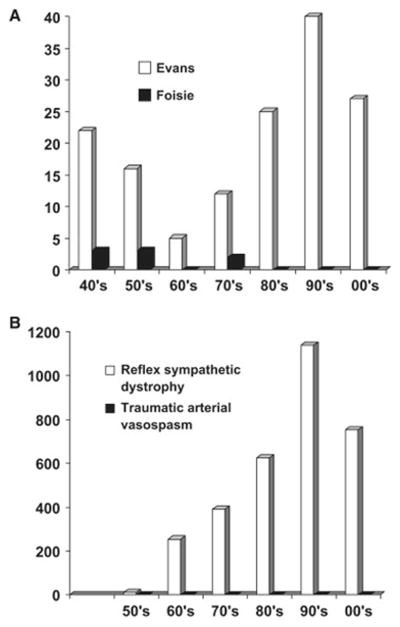

Post-World War II, building on the accumulated knowledge of the military doctors of the previous decades, two proposals for the underlying mechanisms of causalgia / algodystrophy were published within one year of each other. One got immense traction and dominated the research culture until well after the end of the 20th century; the other the received next to no notice until a decade into the 21st century.38

In 1946-47, James Evans, a Boston physician at Lahey Clinic in Burlington, Massachusetts, proposed in a series of four papers that the underlying source of pain maintenance and dystrophy in causalgia-affected limbs were sympathetic reflexes; he concluded that “stimulation of the sympathetic… rubor, pallor, or a mixture of both, sweating, and atrophy…” in addition to intense suffering were characteristic features.38, 1, 5, 9, 6, 8, 10, 26, 2, 16, 3 Inspired by William Livingston’s 1943 Pain Mechanisms paper on central summation where self-sustaining “reverberating circuits” in spinal cord interneurons that relay signals between sensory and motor neurons reach an activating threshold and send pain signals to the brain, Lorento de No’s “vicious circle” of prolonged pain impulses activating sympathetic vascular spasms and increasing swelling, and James Mackenzie’s “irritable focus” of an inflamed internal organ activating a shared spinal cord zone and creating referred pain in a more superficial body location, Evans posited that injury-associated excessive activity in the sensory peripheral nervous system would spread through an “internuncial pool” of hyperactive spinal neurons in the central nervous system and stimulate the sympathetic nervous system; this heightened sympathetic motor activity would create arterial spasms and increase swelling and disproportionate pain.38, 2, 3

He termed the condition Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy, as he concluded that a sympathetic reflex arc maintains the condition, running from sensory organ to sensory neuron to spinal cord interneuron to sympathetic motor neuron to effector such as a muscle or blood vessel.38, 1, 5, 9, 6, 8, 10, 26, 2,16 RSD was the primary term used for the condition for 50 years until the name change to CRPS-I in the 1990s.2, 16

Most of Evans’ patients developed the condition after a fracture, sprain, vascular complication, amputation, joint or bone inflammation, lacerations, other minor injuries including bruising, and postural problems of the foot.38, 1, 10, 3 He utilized sympathetic nerve blocks as treatment and symptoms improved, which solidified the view that abnormal sympathetic activity was associated with and likely central to the disorder; sympathetic nerve blockades were seen as both diagnostic and curative for the sympathetically maintained pain of RSD. 26, 3 However, as time and research has continued on, the fact has become clear that many CRPS patients do not respond positively to sympathetic nerve blockades, particularly for those with persistent CRPS, and recent studies have not demonstrated that the sympathetically maintained reflex arc is involved in every case.38, 26, 21, 39

In 1947, a second proposed mechanism was published by Boston City Hospital surgeon Philip Foisie (1896-1996), who served as a military doctor at the 129th General Hospital in the European Theater during WW2; he concluded that persistent low-grade arterial vasospasms after a tissue injury were impairing circulation and creating a constellation of symptoms via loss of nutritional blood supply, including severe pain, swelling, muscle and bone loss, joint stiffness, limited range of motion, and allodynia.38, 40, 1 Likely influenced by Lireche’s work recalling ischemia similarities, Foisie posited these spasms were happening in smaller arterioles rather than in large vessels that could cause necrosis of tissues as seen in conditions like compartment syndrome; his paper described how soldiers who developed the condition were not those with “wide open” wounds, but rather fractures, minor gunshot or shell fragment wounds, soft-tissue injuries, and especially in compression injuries where intracompartmental pressure increased.38, 40, 1

What Evans termed Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy, Foisie called Traumatic Arterial Vasospasm.38, 40, 1 While both hypotheses included the sympathetic nervous system and vasospasms and ischemia and both recommended sympathetic nerve blocks as treatment, it was their views of centrality of the sympathetic system to the condition that differed.38, 1 In Evan’s proposal, the sympathetic system’s abnormally increased activity was foundational and critical to maintain the vicious circle of the condition.38, 1 In Foisie’s proposal, the injury itself induced the vasospasm, and so increased sympathetic activity could occur but was not required.38, 1

As knowledge of CRPS and its underpinning expands, and it is known that in early onset CRPS sympathetic activity is blunted rather than enhanced, that vasospasms can be maintained even as sympathetic activity is blunted, and that the entirely secondary effects of dystrophy only impact about 15% of those with the condition, Foisie’s thought-process gains more recognition in modern times by today’s researchers; it is often under the term of ischemia-reperfusion injuries rather than traumatic vasospasm.38, 16, 21

38 Image Credit: Coderre, Complex regional pain syndrome – type I: What’s in a name? (Journal of Pain, 2010)

1950-70s: Bonica, IASP, the RSD Stages, and the Name We Know Today

In 1947, Steinbrocker proposed the name Shoulder-Hand Syndrome, and in 1953 he started using oral corticosteroids to treat the condition.2, 22 During the Korean War (1950-1953), thermography was put to practical use on American soldiers suspected of having RSD by Lawson.2 In 1974, Hannington-Kiff began utilizing IV blocks with guanethidine, a catecholamine reducer.2, 22 In the 1970s, Franklin Kozin in the USA and Serre in France began including Nuclear Scans and Three Phase Nuclear Bone Scans while attempting to diagnose the condition, and the Three Phase scans are still often used today.2, 22

In 1986, William Roberts introduced the terms sympathetically maintained pain (which is dependent on sympathetic motor fibers and can be relieved by a nerve block) and sympathetically independent pain (which is independent of sympathetic motor fibers and cannot be relieved by a nerve block); this terminology became highly popular with researchers, but the phrases have gradually faded as the predominant view that the sympathetic nervous system was the crucial foundation of the condition has been revealed to be inaccurate.38, 6, 26, 22, 21 Though individuals will likely still hear the SMP and SIP terms in relation to CRPS, more common terms with modern understanding would be centralized pain or central sensitization, central mechanisms, and peripheral mechanisms.

In 1953, John Bonica—the founder of the International Association for the Study of Pain— published his book “The Management of Pain” and with that the beginnings of Algology—Pain Management—broke off as an offshoot of Anesthesiology.1

The IASP—founded in 1973—was the first foundation dedicated exclusively to the study of pain, and one of its primary objectives was to standardize the classification of pain, particularly chronic pain.32 RSD was one that was difficult to categorize and classify, and several expert consensus groups have met over the decades to better clarify the CRPS research and clinical criteria.32

Bonica proposed a three stage framework for RSD: Stage 1 acute, characterized by inflammation, heat, sweating, and swelling, occurring three months or less after onset; Stage 2 dystrophic, characterized by severe pain, cyanotic discoloration, sweating, reduced range of motion and strength, decreased hair growth, and swollen skin; and Stage 3 atrophic, characterized by less severe but still disabling pain, thin, dry, cold, sometimes ulcerated skin, mottling, and cyanosis, with reduced range of motion and strength, as well as regional osteoporosis, occurring six weeks or more after onset.32, 10 Based on his personal experience treating the condition, he was of the opinion that these stages were sequential.32, 23

Due to the advancement of study on this condition and the accumulation of evidence, it is now known that this staging is not sequential, but there does appear to be three subcategories of CRPS presentation that mostly overlap with Bonica’s groupings: those with primarily vasomotor dysfunction but an otherwise limited syndrome, those with primarily neuropathic pain/sensory dysfunction but an otherwise limited syndrome, and those with a wide array of CRPS features and a florid syndrome. 23 All of these subgroups have a similar pain duration, which argues against a sequential staging view, though the groups themselves do appear to exist. 23

In 1994, Bonica proposed renaming RSD and causalgia to Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) to bring into focus the regional nature of the pain in an anatomical area rather than in alignment with nerve roots; complex was added to demonstrate the diversity of the clinical aspects and pathogenic components, and dystrophy was dropped as it became clear only a small segment of the population experienced it and it was entirely secondary.32, 10

1990s: Expert Consensus Groups

As my readers are likely well-aware, there is currently no “gold standard” test to definitively prove if an individual has CRPS; diagnosis relies on physician expertise, careful patient history taking, and reported symptoms and visible signs. This requires experts in the field to gather and come to an agreement on what the diagnostic criteria ought to be, then a period of utilizing those criteria, gathering data, and running validation studies to determine accuracy, and making adjustments at following expert consensus groups as necessary to further refine the criteria.1, 16, 23

The first IASP conference took place in Schloss Rettershof near Frankfurt, Germany in 1988, but its focus was on the broader topic of pain syndromes rather than CRPS specifically; in 1990, the IASP symposium in Mainz, Germany discussed the pathophysiology of RSD. In 1994, the IASP consensus group happened in Orlando, Florida and brought us the first widely recognized diagnostic criteria for CRPS.1, 8, 26, 16, 23 The Orlando Consensus is where RSD became CRPS-I and causalgia became CRPS-II, discriminating between those without and with obvious nerve damage.1, 8, 16 The Orlando Criteria had a high sensitivity at 0.98 (ability to correctly identify those with the condition) but a low specificity at 0.36 (incorrectly identified those with another condition—most often diabetic neuropathy—with CRPS); approximately 40% of those with diabetic neuropathy would have fulfilled the Orlando Criteria.1, 8, 41 Another problem with the Orlando Criteria was that they were entirely based on self-reported symptoms and not on objective signs or data.1, 41

Another diagnostic tool was presented in 1993 by a Dutch surgeon named Peter Veldman.1 Veldman was an opponent of the (now discredited) subsequent RSD stages and had instead identified subgroups of “cold” and “warm” cases, which have thus far withstood the test of time.1 Foisie’s hypothesis—now ischemia-reperfusion injury cycles—would account for both the “cold” ischemia-dominant and “warm” reperfusion-dominant cases, as well as aid in reframing the stages as individuals move from “warm” to “cold” cases.38 It appears the longer an individual has CRPS, the more likely they are to move from a “warm” case to a “cold” one, though the vast majority of patients start as “warm” cases and not everyone makes the transition to a “cold” one.

In 1997, another expert consensus group got together to create the Malibu Guidelines, whose goal was to make a graded functional restoration via physical therapy operational process. 23 While the Malibu Guidelines did address multiple types of interventions, they did not offer specifics on ideal sequencing or duration; additionally, another problem with the guidelines was their strict adherence to a rapid timeline, where each stage of the restoration treatment should be progressed through in two weeks or less, which many found to be unrealistic or overly rigid. 23 Finally, the Malibu Guidelines recommended that all medications, blocks, and mental health therapy should be reserved as a final option on a linear path for those who do not make progress with physical therapy alone, rather than offering any of these aids from the beginning. 23

Due to these criticisms of the functional restoration guidelines, another expert consensus group met in Minneapolis in 2001. 23 The Minneapolis Guidelines recommended the use of concurrent (as opposed to linear) pathways, offering patients access to physical therapy, medication management, and psychotherapy simultaneously. 23 They also reduced the focus on adherence to a rigid timeline, instead highlighting functionality, and became more permissive in offering different kinds of pain relief modalities, such as medications and nerve blocks. 23

In 1999, Harden and Bruel carried out a validation study on the Orlando Criteria to test its ability to correctly classify within the study sample and its degree of generalizability of the study onto an entire population.1, 23 This led to a significant revision of the Orlando Criteria in 2003 at the Budapest Consensus group, which created the Budapest Criteria used to diagnose CRPS today.1, 8, 41, 23 This revision significantly improved (to 0.69) the criteria’s ability to weed out those who are experiencing a different condition while retaining its high sensitivity (0.85) to those who do have CRPS; it also added objective signs that must be visible to the physician at the time of diagnosis.1 A 2010 re-validation study of the Budapest criteria found it retained exceptional sensitivity (0.99) and greatly improved the specificity (0.68);8 Harden et al states this is “better than most objective diagnostic tests.” 23

In 2010 the CRPS Severity Score was developed as an extension of the Budapest Criteria, where each individual criteria component is utilized to create a continuous index of symptom severity, with a higher score indicating a more severely affected individual. 23 It is expected that those with acute CRPS will see more fluctuation, while those with persistent CRPS will have relatively stable scores. 23

As recently as 2021, the Valencia Consensus group met in Italy to address a few pragmatic criteria clarifications without altering the criteria themselves, primarily regarding subtype classifications. 23 These issues fell into three main categories: the diagnostic parent in the ICD-11 would move from “focal or segmental autonomic disorder” to “chronic primary pain”; clarifications on diagnostic procedure, such as assessing spreading, asymmetry, sensory components, and fluctuating symptoms; and CRPS subtypes, particularly the newly added CRPS with Remission of Some Features for those who once met the full criteria but no longer do but are not considered Resolved cases.

Post-2000: Global War on Terror, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and the Sex Ratio

Modern-day soldiers still develop CRPS; Operation Iraqi Freedom (2003-2011) veterans who are seen in pain clinics were found to have a CRPS rate of 4.3%.3 Soldiers with penetrating blast wounds from car bombs, land mines, gunshots, and grenades are not exempt from potentially developing this condition, despite greatly improved triaging and battlefield anesthesia protocols since the Vietnam War reducing the likelihood of blast-induced chronic pain.3 The current (as of 2022) rate of CRPS-II in wounded soldiers is 1-2% of all peripheral nerve injuries.3

As research into CRPS continues and our understanding of the science behind it both broadens and deepens and women’s health is taken more seriously, many people who would have previously been dismissed are now being diagnosed, changing what was historically considered a condition that primarily affected young male soldiers on the active battlefield to one that primarily affects females, particularly those in their middle ages, at a ratio of about 3-6:1, with the ratio getting steeper as cases move into the more severe, persistent end of the spectrum.32 This recent-ish development in who is being diagnosed with CRPS in the last several decades has changed the conversation around the condition.

The discourse persists between those who hold that the CRPS label (more specifically CRPS-I, without demonstrable nerve damage) should be “abandoned” and recategorized as Functional Pain Disorder, a subset of FNDs—along with other conditions they state have “vague, non-anatomic symptoms” like POTS, MCAS, hEDS, fibromyalgia, CFS, and IBS—and those who promote that it is more likely a neuro-autoimmune condition—given findings of chronic focal axonal injuries, strong associations with neuropathy, asthma, menstrual disorders, migraines, and osteoporosis, and a large subset with autoantibodies against the autonomic receptors for β2-adrenergic, α-1a adrenergic, and muscarinic-2; the adjacent debate over the underpinning mechanisms of FNDs also persists with primary models being cognitive-behavioral, dissociative, psychodynamic, Bayesian predictive coding, and neurobiologic.26, 37, 41, 42 Meanwhile, a significant swathe of providers are simply unaware of CRPS at all or have only a glancing familiarity with it.

Treatments for CRPS have expanded considerably since its discovery, and today sympathectomy and amputation are generally not recommended and considered a last resort. While the prognosis for persistent CRPS cases remains challenging, a great many interventions are now available to improve patients’ quality of life—including providing affected individuals and their loved ones with evidence-based educational materials to help them better understand what they are experiencing and improve their ability to make informed decisions in their own best interest.

Closing

The history of CRPS is complicated, with multiple names applied to it over various decades and countries, and a growing knowledge-base as awareness of the condition expands. As shown in a few key examples throughout this article, not all discoveries regarding the condition end up being accurate, even if they gained a wide amount of traction, particularly regarding the centrality of a hyperactive sympathetic nervous system (which, while it can affect severity of the condition, is not required to maintain it) and the three sequential CRPS stages (though the three subgroups described in the stages do appear to exist nonsequentially). More and more evidence accumulates as each year passes, permitting greater accuracy and a more comprehensive outlook.

At some point in the future, after the pathophysiology is more firmly identified, Complex Regional Pain Syndrome may undergo another name change that speaks more specifically to its underpinning mechanisms.

Sometimes in order to look forward, it is important to first look backward and understand the foundation on which we stand to better comprehend the patterns that tend to repeat, the paths that may appear ahead, and the decisions we may be faced with as history’s cyclical turn comes around again. Many of the great leaps of knowledge in CRPS’s history are intrinsically entwined with some of the darkest, bloodiest, most emotionally intense battles of the major wars in the last 200 years and the king who reigned over a widespread religious massacre from nearly half a millennium ago. These were exceptionally personally taxing periods that stretched humanity’s capacity to endure to its fullest measure. One can only speculate what the next major leap in the CRPS knowledge base will entail when historians look back to put it into context and what the personal cost will be for those individual patients whose life experience contributes to those discoveries.

Presently, while the climate crisis looms ever larger in the background, animating ethno-nationalists to defend isolationist policies and reject immigration, American research grants are being slashed as federal departments are being hollowed out and entire offices eliminated, social safety nets are being destroyed as educational and health systems overload to their breaking points while adequate insurance coverage gets pushed further out of reach for a significant portion of the US populace with a particular impact on the “federally able-bodied” disabled, worker protections get gutted while wages are suppressed and costs of living rise, and the country with the world’s most powerful military takes an increasingly aggressive approach to national and international relations. In this setting, religious fundamentalism secures a firmer grasp on American government and Christian Dominionism, a supremacist theocratic movement, gains momentum and reach while losing hesitance it once held over achieving its authoritarian aims: a nation whose laws are founded on a strict, literal interpretation of biblical text and are enforced by the full power of the state, so that the entire citizenry must submit to and obey their fire and brimstone version of God or be punished by the government. How all this will impact the future of CRPS research remains to be seen.

Thanks for sticking with me, I hope you learned something, and I hope to see you next time.

References

- Iolascon et al, Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) type I: historical perspective and critical issues (Clinical Cases in MIneral and Bone Metabolism, 2016) ↩︎

- Burning Nights (n.d.) History of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. https://www.burningnightscrps.org/crps/crps-information/what-is-crps/history-of-crps/ ↩︎

- Nelson et al, Causalgia: a military pain syndrome (Journal of Neurosurgery, 2022) ↩︎

- Pearce, Silas Weir Mitchell and causalgia (Hektoen International, 2022) ↩︎

- Castillo-Guzman et al, Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), a review (Medicina Universitaria, 2015) ↩︎

- Okumo et al, Senso-Immunologic Prospects for Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Treatment (Frontiers in Immunology, 2022) ↩︎

- Alhammadi, Alqahtani, A case of truncal complex regional pain syndrome: literature review (Annals of Medicine and Surgery, 2024) ↩︎

- Gaulke, Bennett, Complex Regional Pain Syndrome – A Medico-Legal Review (Workers’ Compensation Law, 2015) ↩︎

- Shim et al, Complex regional pain syndrome: a narrative review for the practising clinician (British Journal of Anaesthesia, 2019) ↩︎

- Rozycki, Tobias, Suffering as a Diagnostic Indicator (Pain Management – Practices, Novel Therapies and Bioactives, 2020) ↩︎

- Echlin et al, OBSERVATIONS ON “MAJOR” AND “MINOR” CAUSALGIA (Neurology and Psychiatry, 1949) ↩︎

- Lau, Chung, Silas Weir Mitchell, MD: the physician who discovered causalgia (The Journal of Hand Surgery, 2004) ↩︎

- Koehler, Lanska, Mitchell’s influence on European studies of peripheral nerve injuries during World War I (Journal of the History of Neuroscience, 2004) ↩︎

- Kline, Silas Weir Mitchell and “The Strange Case of George Dedlow” (Journal of Neurosurgery, 2016) ↩︎

- Schott, Complex? Regional? Pain? Syndrome? (Practical Neurology, 2007) ↩︎

- Harden et al, Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: Practical Diagnostic and Treatment Guidelines, 4th Edition (Pain Medicine, 2013) ↩︎

- Klifto, Dellon, Silas Weir Mitchell, MD, LLD, FRC: Neurological Evaluation and Rehabilitation of the Injured Upper Extremity (Hand, 2019) ↩︎

- Mitchell et al, The Classic: Gunshot Wounds and Other Injuries of Nerves (Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 1982) ↩︎

- Kalikstein, Rosen, S. Weir Mitchell, Successes and Failures of the Father of American Neurology (History of Neurology, 2019) ↩︎

- Pearlstein, Cutter, Causalgia: ‘The Most Terrible of All the Tortures’ (National Museum of Health and Medicine, n.d.) ↩︎

- Rho et al, Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (Concise Review for Clinicians, 2002) ↩︎

- PARC (n.d.) HISTORY of RSD/CRPS. https://www.rsdcanada.org/parc/english/RSD-CRPS/history.htm ↩︎

- Harden et al, Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: Practical Diagnostic and Treatment Guidelines, 5th Edition (Pain Medicine, 2022) ↩︎

- Richards, Causalgia: A Centennial Review (JAMA Neurology, 1967) ↩︎

- Cervetti, S. Weir Mitchell Representing “a hell of pain”: From Civil War to Rest Cure (Arizona Quarterly: A Journal of American Literature, Culture, and Theory, 2003) ↩︎

- Chang et al, Complex regional pain syndrome – Autoimmune or functional neurologic syndrome (Journal of Translational Autoimmunity, 2021) ↩︎

- Oaklander, Fields, Is reflex sympathetic dystrophy/complex regional pain syndrome type I a small-fiber neuropathy? (Annals of Neurology, 2009) ↩︎

- Bennett, Brookoff, Complex Regional Pain Syndromes (Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy and Causalgia) and Spinal Cord Stimulation (Pain Medicine, 2006) ↩︎

- Canale, Civil War Medicine From the Perspective of S. Weir Mitchell’s “The Case of George Dedlow” (Journal of the History of Neurosciences, 2002) ↩︎

- Goldberg, Beyond “The Yellow Wallpaper”: Silas Weir Mitchell, Doctor and Poet (The New York Academy of Medicine Library Blog, 2016) ↩︎

- Pearce, Silas Weir Mitchell and the “rest cure” (Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 2002) ↩︎

- Gelfand, Dreams: Charcot’s Last Words on Hysteria (Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 2024) ↩︎

- Cooper, Clark, Neuroinflammation, Neuroautoimmunity, and the Co-Morbidities of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology, 2012) ↩︎

- Perez et al, Neuroimaging in Functional Neurological Disorder: State of the Field and Research Agenda (NeuroImage Clinical, 2021) ↩︎

- Da Mota Gomes, Engelhardt, A neurological bias in the history of hysteria: from the womb to the nervous system and Charcot (Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria, 2014) ↩︎

- Brigo, The Chartographer of Hysteria and Fibromyalgia Tender Points (Archives of Rheumatology, 2014) ↩︎

- Oaklander, RSD/CRPS: The end of the beginning (Pain, 2009) ↩︎

- Coderre, Complex regional pain syndrome – type I: What’s in a name? (Journal of Pain, 2010) ↩︎

- Schott, MECHANISMS OF CAUSALGIA AND RELATED CLINICAL CONDITIONS: THE ROLE OF THE CENTRAL AND OF THE SYMPATHETIC NERVOUS SYSTEMS (Brain, 1986) ↩︎

- Foisie, Traumatic Arterial Vasospasm (New England Journal of Medicine, 1947) ↩︎

- Misidou, Papagoras, Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: An update (Mediterranean Journal of Rheumatology, 2019) ↩︎

- Mavroudis et al, Understanding Functional Neurological Disorder: Recent Insights and Diagnostic Challenges (International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2024) ↩︎

Subscribe if interested in email notifications for new content uploads.